O.U.R. Children’s Safety and Success Project

The Girl in the Newspaper:

A Personal Reflection

on Safety

I had a normal and happy childhood. I owe much of that to my parents, who raised me to be a child first and a child with hearing loss second. A little of it is due to the fact that I grew up in a rather boring suburb of the Twin Cities where not much happened. However, there were two glaring instances where, even in the seemingly idyllic world found in many Midwestern suburbs, dangers lurked unknown to my parents and especially to me.

Following an Adult’s Direction

The first instance occurred when I was nine. It was summer and my very best friend and I were out with her mom grocery shopping. We got permission to cross the parking lot of the strip mall to go to the corner drugstore to look at toys and buy candy. As we left the grocery store and headed towards the drugstore, a man in a white car pulled up and rolled down his passenger car window. From his driver seat, he asked us for directions to the interstate. I distinctly remember he had a scraggly yellow beard, wore sunglasses, and the car engine was running. Rather than backing away and immediately finding the responsible adult (who was maybe 200 feet away), I took a step toward the car. I leaned in closer, almost across the threshold of the passenger window and asked him to repeat the question. I hadn’t heard what he asked. The car was noisy and he had a beard, which blocked any visual cues. My gaze was drawn downward and it became immediately apparent that he was exposing himself to me. At that point, I quickly stepped back and the man drove away.

In the grand scheme of things, the indecent exposure was relatively harmless. While memorable, I wasn’t scarred for life. However, the context of the situation is quite chilling. Growing up,we are told about the dangers of talking to strangers and to immediately walk (or run) away from the situation. I was taught something similar by my own parents. At the same time, I was also taught to be a good advocate for myself. I was doing the “right” thing by politely asking an adult to repeat himself and changing my body position to better hear what was said. Unfortunately, I ignored any warning bells about why a strange man asking nine-year-old girls for directions to the interstate.

Um,hello?

Who is Getting What Private Information?

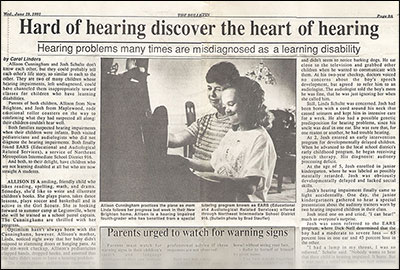

The second instance related to an event when I was in fourth grade. A local newspaper reporter had come to our house to write an article about my accomplishments as a child growing up with hearing loss. (I was the only child from my school district with hearing loss, so I was a bit of an anomaly.)The newspaper featured the article and a picture of me playing the piano and sporting my ugly mullet perm. The story went into a scrapbook, where it was quickly forgotten.

When I was a junior in high school, my parents received a letter from the Minnesota Justice Department. They discovered that an imprisoned pedophile had shared a list of children with other inmates. My name was on the list, as well as the town in which I lived and the word “deaf” scrawled next to my name. The pedophile was able to obtain all of the information based on the article that had been written about me several years earlier.

Now that I’m a practicing audiologist, I look at the situations very differently. I could write an entire article addressing ways to help your child become safer,but I don’t feel particularly qualified to do so. I can however, offer my insight into why children with hearing loss are more vulnerable to these dangers. As highlighted in my newspaper incident, predators may view a child with a hearing loss as “differently-abled.” It also highlights a cautionary tale of how much information parents should allow to be shared regarding their children, particularly in the age of social networking. Think how much faster and further information about a child might spread in today’s faster-paced world.

Intentional, Direct Teaching

I do think much about safety skillscomes down to language. Many of us know that children with hearing loss don’t have the same access to “world knowledge” as children with normal hearing do. As a result, I think deaf and hard of hearing children can be perceived as more gullible. Eventhose kids with age appropriate speech and language skills may have underdeveloped skills in other areas. They may struggle with pragmatic skills (the ability to understand how context contributes to the meaning of a situation). The development of skilled pragmatics is subtle and more difficult to achieve, but it’s what lends any kind of “street cred” to your children with hearing loss.

Role-playing can be extremely advantageous in developing pragmatic skills and specifically skills in understanding what a dangerous situation looks like and what should be done in different scenarios. As a child of the 80’s and 90’s, I remember the D.A.R.E. campaign’s motto: “Just Say No to Drugs.” We had police officers come into our school and spend a considerable amount of time role-playing and giving us examples of what to do when offered drugs or alcohol. I distinctly remember giving the “cold shoulder” and “just saying no” because those were phrases that were taught to me by an adult. It provided a language and context that ishelpful for any child, and particularly a child with hearing loss.

Editor’s note:

This article is reflection of the author’s personal experience and views and does not reflect the views and opinions of Children’s Hospital Colorado.

The OUR Project hosts a monthly conference call to address ways that our chapters can assist parents in Observing, Understanding, and Responding to our children related to experiences of maltreatment. We are currently focusing on prevention. Contact Janet DesGeorges for the monthly teleconference information at parentadvocate@handsandvoices.org. If you would like to learn how to keep your child safe from maltreatment:

- Go to: http://deafed-childabuse-neglect-col.wiki.educ.msu.edu/Home

- Read and share the “Silence is NOT an Option” documents with individuals who interact with your children

- Develop a “safety plan” for your family (http://www.kidpower.org/library/article/special-needs/)

Home

Home