|

In a Perfect World

You Can Feel a Lullaby

By Leeanne Seaver © 2010

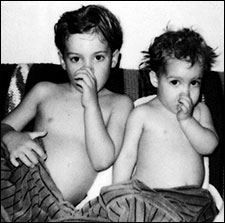

Dane & Kody, ready for bed From the time he was about six months old, my son Dane put a chubby little hand up to my face when I sang to him. He held it there against my cheek until his arm drooped like his eyelids as he nodded off. I wouldn’t know for well over another year that he was not actually hearing my songs. In retrospect, this would turn out to be the sole benefit of his late identification—he was 19 months old when we finally found out he was deaf. The agony of realization that he hadn’t heard a thing I’d said was consoled at least in a small way by my certain knowledge that he loved to be sung to sleep. He was experiencing the feeling of a lullaby…his head against my heart…the synergy between us. The ritual of the lullaby was no less sacred because he couldn’t hear it. This was an early lesson in mothering a deaf child: look beyond your understanding…there’s so much more to see.

In fairness, it must be acknowledged that not every baby has to be sung to sleep. Case in point: my second son, Dakota (nicknamed Kody), who happens to have normal hearing. He liked being sung to, rocked and cuddled, but when it was time for sleep, please just put him in the crib. We discovered this after three weeks or so of what we thought was colic during which time my husband, Tom, dutifully walked that screaming infant from 9pm to 1:30am every single night, until both son and father (in that order) collapsed into sleep. About week four, Tom had reached the end of his wits and surrendered Kody to his crib just as the caterwauling began. Just as quickly it stopped. We both leaned in, checked to see if he was still breathing, then counted his respirations, loosened his blankets, monitored the situation for about 30 minutes before concluding that he was, beyond all imagining, asleep. So for this little guy, the bedtime routine would be entirely different. Who knew?! But I missed lullabies.

Parents need lullabies as much as children do, to my way of thinking. So how does this work if the parent is ASL/Deaf—especially since the goal is to get those little eyes closed? I posed the question to Henri, our Deaf mentor/adopted brother who offered, “A lot of deaf people hum…just keep the baby’s head on your chest so he can feel you.” I asked if his hearing mother sang to him. “Oh yeah, she did, and I found the vibration of her voice on her chest and stomach loving. Knocked me out every time,” he remembered. To me, it’s such a nice thought that even without any eye contact, or without any sound at all, after hearing aids or cochlear implants are set in their chargers for the night, parents and their babies are still communicating some of the most important stuff they have to share with each other.

I can remember the last time I sang and rocked Dane to sleep. He was almost too big to carry. It had been a very long time since we’d indulged in the old routine, and we both knew he’d outgrown it. But new rituals, just as precious, had replaced it, like how he would climb up on my lap, put his hands on my face and pull it to him so we were looking squarely into each other’s eyes. This was reserved for times when sharing and understanding each other went deeper than words. It was not a lullaby, but it always made my heart sing. |