Home

Home- About H&V

- Resources

- Services

- Chapters

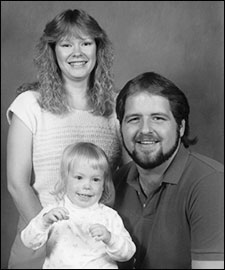

Two year old Megan with parents Mark and Ginny Burgess

Two year old Megan with parents Mark and Ginny BurgessI was born in 1986 with right-sided microtia and atresia as well as a maximum unilateral conductive hearing loss, long before universal newborn hearing screening, Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI), and fantastic parent support groups such as Hands & Voices. As a Doctor of Audiology Candidate aspiring to work with children and their families, I am more than grateful for the development, leadership, and advocacy of such organizations. I am even more appreciative of the hard work, dedication, and love that my parents, Mark and Ginny Burgess, have provided over my lifetime. Even though my parents did not receive the official diagnosis of “microtia and atresia” until I was fifteen years old, they advocated for me and my hearing loss every day without much support or direction from others. I would like to thank my parents for all that they have and will continue to do for me. While I would love to acknowledge all of the small things, as well as the larger more difficult processes, that would take me a lifetime. Consequently, I would like to share just a piece of our story.

When my parents discovered that I was unable to localize sounds, they encouraged me to draw pictures of different rooms in the house as well as the front and backyards. They would then post the picture of their current location on the refrigerator so that if I ever needed to find either one of them, I could simply go to the kitchen and find the picture that I had drawn. Looking back, the process of drawing the simple pictures taught me that I needed to advocate for myself and that my parents would support me along the way. I learned then that I could not simply yell, “Mom, where are you?” and have her respond, “Over here!” because of my inability to localize. As a result, I learned to seek out the information by making the extra steps to the kitchen to find the picture on the fridge. Further, it made me appreciate their willingness to take the extra time to change out the picture on the fridge even if they were only stepping out into the garden for a few minutes. It was simply a part of our daily routine.

When I entered school, the standard request year-after-year was for my parents to ask that I sit in the front of the classroom with my left ear facing the teacher. My parents would report my hearing loss on the school’s health information card; unfortunately, due to privacy laws, that useful information was never provided to the classroom teachers. Had my parents not requested the seating arrangement, my teachers may have never even known that I had a hearing loss. FM systems, IEPs, and closed-captioning were foreign concepts until I went to a college information fair my junior year in high school. After meeting with the disability services representative at the college and learning that I would need a 504 plan to be eligible for any services post high school, my parents met with the principal of the high school to complete the paperwork. It was a long and grueling process because I had never asked for anything more than preferential seating, and the school questioned the request because of my high academic achievements. Needless to say, two weeks before I graduated valedictorian, my parents advocated long and hard enough to obtain a 504 so that I would have the opportunity to receive accommodations in college.

Another aspect of the yearly “routine” was the love, support, and encouragement provided by my parents at our visits to the otolaryngologist (ENT) and audiologist. My parents were not concerned with the appearance of my ear but they always pursued the possibility of restoring my hearing. Years before the advent of the BAHA, my parents were told that my facial nerve intercepted the cavity of my middle ear space in a way that would make surgery to restore my hearing more than difficult, risking paralysis of the facial nerve; however, given time and growing factors, it was a possibility that the nerve would move out of the critical area for surgery. As a result, we saw the ENT yearly for repeated CT scans and discussions about creating a middle ear space. Unfortunately (in some ways), the facial nerve paralysis was always a discouraging factor. Following our appointments, my parents and I would have serious conversations filled with tears, “we love you,” and “If there is anything we can ever do, we will go to the ends of the Earth to do it,” and hugs. This was the fortunate part of that routine. My parents loved me and supported me regardless. My right ear was simply my right ear, and a part of who I am.

Last year, I decided to complete a six-week trial with a BAHA soft band. Even though I was twenty-three years old, it was important to me that my parents be present for the consultation as well as to provide support throughout the trial period. It was one of the most difficult times of contemplation that I have ever gone through because the BAHA restored audibility to my right ear; yet, my way of life was to only rely on my left ear. In fact, to describe it plainly, using the BAHA made me feel like I was “overhearing.” Even though the BAHA was a probable solution for my hearing loss (what my parents had been seeking for my lifetime), it was not the solution for me. When I realized that two ears weren’t better than one (in my case) I had to rely on my parents to remind me that my hearing loss is part of who I am. They encouraged me, reminding me that we had been down similar paths before. Simply because I didn’t want the BAHA then, didn’t mean that there isn’t another solution somewhere in the future-- just as they routinely reminded themselves throughout our journey.

Time and time again, with the help and advocacy of my parents, I was able to accept my hearing loss and move forward. They taught me to advocate for myself and to succeed academically despite my differences. I am who I am because of my parents. Thanks, Mom and Dad! I couldn’t have done it without you! Happy Mother’s and Father’s Day!